Pollsters have had a good

independence referendum. However, improved explanations about why voters

have swung to ‘Yes’ would be helpful.

This blog discusses public attitude change and how it might be better explained during a future EU referendum campaign.

Opinion pollsters have added insight and direction to an engaging campaign. Without the polls we would be unaware just how close the contest had become, lost in a fog on punditry. We would be subject to endless claims

and counter-claims from each lobby about who was really speaking for the people. Polling keeps politicians honest, telling us

about the evolving credibility of each side’s message. Interviews and focus groups with voters may

have their own value, but they leave us little wiser about the overall outcome

of the event. By contrast, polling forecasts

have moved financial markets, changed campaign strategies, perhaps even caused

the No lobby to concede ‘Devo Max’ to the Scots. Given the increasing demand for polling

predictions, and the internet technologies that make the supply of polls cheaper,

we should expect increased polling activity if and when an EU Referendum is

called. But the product itself can

be improved.

Whilst the Scottish experience has been great news for the

pollsters, it has also given them a couple of headaches. Firstly, it may go horribly wrong by Friday

morning. Any celebrations of their

impact could prove premature if the actual result reveals an industry-wide

miscalculation. Given that the

independence ballot is a one-off, methods cannot be tweaked from previous experiences

to correct for non-random (systemic) error.

Polling companies are therefore less

sure than usual about the accuracy of their surveys, particularly those using

online panels that rely upon heavy weighting to the initial samples. The +/- 3 point ‘margin of random sampling error’ may not tell the

full story of polling reliability. To

the pollsters’ credit, they have been both honest and humble about their

methods, taking every opportunity to raise their own self-doubts about their

figures. An excellent discussion of

referendum polling accuracy can be heard on the BBC Radio 4 More or Less programme, here, and the matter is

well reviewed in a blog by Stephen Fisher here and Anthony Wells here. The general feeling seems to be that, if

anything, pollsters are more likely to be overestimating rather than

underestimating actual support for Yes.

Even if they get it wrong this time, they deserve credit for sticking their

stake in the ground, being open about their methodology so it can be improved

upon in future.

Assuming the pollsters have told us correctly what will

happen, to be confirmed tomorrow, they are less impressive at telling us why it

is happening. Ultimately, what really

matters is change in public attitudes because it’s this change which could

split the United Kingdom apart. Understanding why

support has changed requires a fuller range of survey indicators than the

simple and less reliable self-reports by voters of their own motivations – the questions

which are asked currently. The public

need to be probed in more detail about their national identities, partisanship,

economic evaluations and levels of political trust that are all key causal

variables. Also such indicators need to

be analysed over time rather than as one off measurements, to pick up on trends. Very little of this over time analysis has

been conducted on attitudes towards independence, in part through lack of data. This may explain why it took a shock poll

from YouGov, showing Yes in front for the first time, to jolt public interest

and the No side into serious action, less than two weeks prior to the ballot. Whilst traditional polling based on

individual snapshots of opinion did not see a close race coming,

it was in fact predicted by researchers at Southampton University, using a rare (Bayesian) model of

vote intention based on trends and probabilities. Better partnerships between public facing

polling companies and academics versed in time-series methodologies could

improve the offering and its overall impact.

Understanding underlying trends in support is crucial to

framing the right campaigning strategies on both sides, shedding light on what

is working and what is not.

Misunderstanding of why support has moved, could explain the poor

performance of the No campaign. In a

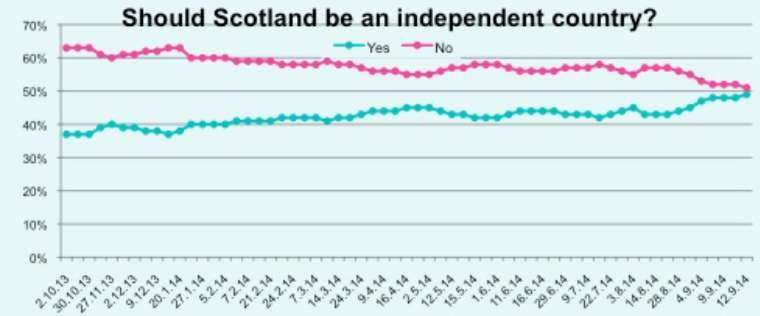

matter of weeks, opinion is now split close to 50/50 between Yes and No, having

been 60/40 against, a shift described by Anthony Wells of YouGov as a ‘real and

sustained large change’. Polls may be

overestimating or underestimating support at any one time, but on the question

of over time trends they are unequivocal.

As the ‘poll of polls’ below shows, this growth in support for

independence has actually been going on for months rather than weeks:

Pollsters and political scientists who specialise in public opinion tend to be conservative about shifts in attitudes, particularly short-term ones. As the Polling Observatory make clear, these can often be nothing more than random noise, artefacts of measurement instruments rather than a significant signal of attitude change. However, long-term change as evident in Scotland cannot be so easily dismissed.

The question of explaining attitude change is also a

theoretical one about how voters form their opinions, extending beyond

practical questions of data and polling methods. The problem here is a lack of clear underlying

theory why individual voters have actually shifted their attitudes. Within some quarters of academia, there is

outright denial that voters possess the capacity to change their views in

response to campaign information, at least in a meaningful way. Dr Rob Johns, writing on the British Election Study website, warned in July – just before the No campaign

started to implode: ‘do not expect major shifts in opinion in the run-up to 18 September and that ‘the millions to be spent on persuading voters between now

and polling day will be largely wasted’.

What appears in hindsight as irresponsible advice, reflects

a gloomy appraisal of the voter. Rather

than behaving in a largely economic (or ‘rational’) fashion by consciously

weighing up the costs and benefits of Yes and No, Johns argues voters develop

their preferences in an irrational or psychological manner, working against

change. Preferences are deeply rooted in

‘early upbringing and personality’. This

idea dates back to the seminal ‘Michigan School’ studies of the American Voter

in the 1950s, an account of electoral behaviour that stressed the role of

‘enduring partisan commitments in shaping attitudes’, formed early in life and

remaining stable through adulthood (Campbell et al. 1960). Despite

concerted attempts in voter studies to revise the Michigan School approach with

more dynamic ‘rational choice’ type models, the older approach has never really

gone away. Indeed national identity

attachment is ingrained in academic literature as the dominant variable for

explaining support for the EU (Hooghe and Marks, 2009). The question is, when significant opinion

change does happen, as it did during the Eurozone crisis in respect of

attitudes towards EU membership, and now again during the Scottish Referendum

campaign, is the Michigan School theory up to the task of explaining it?

Under the Michigan model, when the voter is confronted by

new information, he is likely to become polarised in his existing opinions

because he assimilates news through the prism of his long-standing biases: ‘the

individual is more a rationaliser (of his existing prejudices) than a rational

decision maker’ (Lodge and Taber, 2013:26).

For example, in the Scottish case, the voter who watched the televised

referendum debates, if a nationalist, would tend to dismiss Alistair Darling’s

arguments whilst agreeing with Alex Salmond, without judging the competing

arguments on their merits. The unionist

would behave similarly, blindly agreeing with Darling and rejecting the words

of Salmond. Hence, not much change in

the polls would result. If one side

enjoys a short-term bounce, it is likely to be superficial, dissipating as

voters powerful long-term attachments kick back in.

There is another specific reason why this psychological, non-rational

model theory of the voter is popular in explaining opinion on the Scottish

referendum. Independence is an issue

akin to the question of EU membership, long considered difficult for the public

to appreciate in a thoughtful way.

Academics like to argue that because the economic and constitutional

questions of EU membership (or Scottish independence) are so complex, an

essentially lazy and ill-informed public cannot engage with them. Instead, EU membership or Independence stirs

passions that are not reconcilable with rational discourse – so the argument

goes. These passions are based on national

identities and populist distrust of the governing elite, which combine in a

heady cocktail of emotion. Whenever we

hear the media framing the debate as ‘hearts versus heads’ this line of

thinking is in play. The assumption is

the public cannot reconcile competing (affective-cognitive) dimensions in their

support, meaning their evolving attitudes are unstable, and usually constructed

externally of them. In the simplest

terms, rather than the voter consciously and reasonably weighing up different

aspects of the debate and making informed choices himself, the different

dimensions in his attitudes become mobilised by the media and politicians

instead. And this becomes the

explanation for changing preferences to Yes – the Yes campaign could

effectively mobilise voters key underlying attachments against Westminster,

together with Scottish nationalism. The

No campaign was always likely to struggle to mobilise Scottish voter’s economic

calculus against separation by highlighting its risks. If the Yes campaign wins, it will be said

that hearts have triumphed over minds.

The result was somewhat inevitable and No’s big mistake was allowing the

referendum to happen in the first place.

There is an alternative explanation of why attitudes have

changed in Scotland which gives more credit to the voter. It does not deny that Scottish voters’

beliefs are strongly influenced by their national identity and that many have a

passionate distrust of the British political establishment, nor does it take a

view on the worthiness of these attitudes.

It simply maintains that these emotional aspects of their support are

more closely related to their economic evaluations than the psychological

theory of voting insists. Rather than

voters’ support for independence being structured along two unrelated

dimensions, attitudes are simply a mix of the voters own prior beliefs and new

evaluations. Voters update their prior

beliefs as a ‘running-tally’ of their new evaluations of information, changing

these prior beliefs when they consider the new information to be sufficiently

valuable to affect their interests – and ignoring it if they consider it

invalid (Fiorina, 1981). The voter isn’t

so conditioned by his background and psychological processes, rather he has

subjective views of his own and is capable of making choices. The problem with the No campaign wasn’t

necessarily the dry emphasis on economic and political costs and benefits, but

that the public either didn’t receive sufficient information early enough; they judged

the message too disorganised and confused; or discounted the information because

they distrusted the source. If No loses, it was not inevitable, their arguments weren’t necessarily

wrong but their presentation was. In

particular it needed to come from more trusted sources than the declining Westminster

mainstream elite – perhaps the Scottish voters themselves via a more

grass-roots orientated campaign. (The

importance of grass-roots campaigning and the weakness of mainstream political

parties in influencing their voters is a major lesson for EU referendum campaigners.)

The running-tally explanation of changing attitudes demands

that voter attitudes are modelled over time, to reflect the probability

calculation that voters make between the value of their previous beliefs and

the worth of new information. It

requires long-running time-series data with the same questions asked in each

poll, such as by the monthly British Election Study Continuous Monitoring Survey. New data, new methods and revisionist

theories about the capabilities of voters to make informed choices could all

contribute to make polling on a future EU referendum even more impactful than

the polling on the Scottish independence referendum.

References:

Campbell,

A, Converse, P, Miller, W and Stokes, D.

(1960). The American

Voter. University of Chicago Press.

Fiorina,

M. (1981). Retrospective Voting in American National Elections. New Haven:

Yale University Press.

Hooghe, L and Marks, G. (2009). A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus. British Journal of Political Science, Volume 39, Issue 1, pp 1-23.

Lodge, M and Taber, C. (2013). The Rationalizing Voter. New

York: Cambridge University Press.Hooghe, L and Marks, G. (2009). A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus. British Journal of Political Science, Volume 39, Issue 1, pp 1-23.

My planned PhD thesis is summarised here. It uses the ‘running-tally’ theory and time-series methods to explain why public attitudes have moved so sharply both for and against EU membership in the last ten years, in response to record EU immigration and financial crisis.